I have a very short hiatus between the end of the Spring Semester and the onset of a May Term, during which I’ll be teaching a three-week course on the Spanish Conquest. (As an aside, I’m hoping in that May term to finally pull off having students build a text adventure game, or games, on the course subject.)

During this break, I’ve been grinding through neglected inventories of cases that form the archival core of my current work on popular sexuality in the Spanish Empire. These cases are drawn from the Archivo Nacional del Ecuador (ANE), and are drawn from the Criminales, Civiles, Matrimoniales, Residencias, Fondo Especial, Prisiones, and assorted other Series from the ANE. The most important of the cases are from the Serie Criminales, of which my case set counts some 900 of about 3400 extant criminal cases from the colonial period. The Serie Criminal for the colonial period includes cases dating from 1589-1820, though through the middle decades of the 17th century, there are very few surviving cases. Of the 900 cases I’m using from the Serie Criminales, 333 are sex-related cases, in which the individuals being investigated are accused of sex-related acts. The other 600-odd cases relate to contextually interesting criminal prosecutions: 1. drunkenness; 2. domestic violence; 3. insults; 4. magistrate abuse of power; 5. gambling; 6. horse racing; 7. murder and assault; 8. etc.

I’ve chosen these cases in order to better understand the nature of sex-related prosecutions, and their potential for an ethnohistorical-like investigation of popular sexual norms. I decided in the process of putting together my inventories of cases to keep track of the relative frequencies of sex-related prosecutions in the criminal archive. I then plotted these frequencies across boxes and years. As with many archives, the ANE Serie Criminales is divided into numbered boxes (cajas) full of individual cases folders (expedientes). It is impossible to draw too many conclusions from the cases that have been preserved over the centuries because we have no way of knowing what’s behind the particular preservations. Was part of the archive damaged or destroyed in a previous age? Were some magistrates or notaries better or worse at collecting, preserving, and passing on their files? Likewise, we have no cases from the first 20 years of Quito’s existence as an Audiencia, and only a smattering into the early 18th century.

Nonetheless, charting the cases in my archive does show some interesting trends. So, two charts for you. (Click on each chart to get much larger images.)

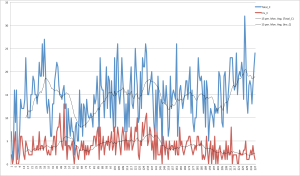

1. Total and Selected Cases, 1601-1820:

This chart includes both raw counts and rolling 15-year averages of case counts for the total Serie Criminales and my 900-case subset. It’s divided by archival box, rather than by case year– which gives an impression of a much more consistent archive size over the years. Note that there are two periods where my selection of cases deviates a bit from the total case trend line: 1. from around box 45-55; and, 2. from box 185 onward. Temporally speaking, boxes 45-55 correspond to the period roughly between 1755 and 1765, the early years of Charles III’s reign (1759-1788). Box 185 onward takes us from 1802-1820, through the end of colonial rule. (Ecuador officially became part of Gran Colombia in 1822, but I’ve truncated at 1820 for convenience only.) This was an era of liberal ascendance and crisis. That said, in the raw counts its visibly the case that cases I find interesting begin to decline in the Box 140s, or around 1790, which corresponds to the end of Charles III’s reign. I should have plotted this with a different trendline. Why a 15 year rolling average? I don’t know, it’s my own experience that 15 years might be a chunk of time that produces a sort-of epoch of prosecutorial priorities.

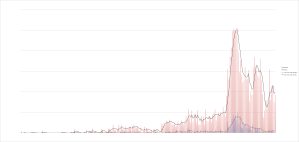

2. Total and Sex-Related Cases by Year, 1601-1820:

Here I’ve changed the x-axis from box to year, and plotted only sex-related cases. It’s much more obvious in this chart that the Serie Criminal is really an archive of the 18th century. The first real uptick in cases begins around 1722, the second around 1743, and the big explosion amps up in 1779. By the way, the second peak corresponds to the first decade of the 19th century. I’ve also included 4-year rolling averages in this chart. Sex-related prosecutions peak in the same general time frame as overall prosecutions peak, but their percentages are anomalously high. As a percentage, sex-related prosecutions peaked in 1788 as 27% of the extant criminal cases in the Serie Criminales. This comports with jail censuses.

You’ll note there is a little bump in the trendline for Sex-Related cases earlier in the 18th century. Right around 1745, when for a cluster of a few years those cases again reached into the 20% range of total cases. What do the 1740s and the 1780s have in common? Well, for one thing they have periods of epidemic disease and natural disaster in common. Could natural disorder account for a rise in sex-related prosecutions, when a reformist government might be interested in making order?

The devil in that question is in the details, and it’s interesting to note that prior to the 1780s, sex-related prosecutions were dominated by instances of forced rape, incest, and cases involving young women. In the 1780s, cases are dominated by descriptions like illicit relationship, concubinage, and adultery. This suggests the state takes a very different interest in sex acts at the point that prosecutions dramatically increase.

What am I doing with these cases?

This project has evolved over time. What I’m actually interested in is both methodological and historical– understanding popular attitudes towards sex through prosecutions. So, I’m taking especially cases of concubinage and adultery and looking at a number of factors. How do magistrate and defendant portrayals of these relationships differ? How long did relationships last before they were brought before legal authorities? What were the circumstances that made relationships prosecutable– what accounted for their transition to notoriety? What I’m finding is that defendants use arguments from customary practice that are similar to legal defenses across the spectrum of criminal and civil litigation. I’m also finding that relationships were very frequently long-lived, often producing children and never drawing the attention of the state until something outside those relationships sparked a conflict. This could be violence, nightly patrols by judicial authorities, commercial disagreements, and any other number of conflicts that had little to do with sex and much to do with other aspects of neighborhood tranquility. What to make of that? The cases paint a picture of toleration without tolerance in popular sexual attitudes in the eighteenth century.

I’m also finding that as the 18th century wears on, the insults people hurl at one another become increasingly tied to racial terms, including those hurled at women. More and more, phrases like “(s)he treated my like a zamba/india” show up. But, that’s another post altogether.

Leave a comment